In 1850, the beleaguered forces of a Maya rebellion gathered at a cenote—a sort of large natural well formed by a sinkhole—named Chan Santa Cruz or Little Holy Cross. Three years earlier the Maya had rebelled against a Yucatan government dominated by Spanish-descended peoples (“whites” in their parlance) in response to a long history of exploitation and discriminatory treatment. From the outset, this conflict, called the “Caste War,” intermingled questions of race, class, and religion.[1] One of the chief instigating factors was a tax levied on Maya to financially support the church along with the practice of charging indigenous people far higher rates for sacramental rites like marriage and baptism.[2] The rebels initially demanded only to be free of this church tax and to have the charges for sacramental services set at a fixed rate common to Maya, “negroes,” and “whites” alike. While the rebellion had initially been successful, the militias of the Yucatan government regrouped and were pressing the Maya rebels hard.

Weary and suffering losses they retreated to the Little Holy Cross cenote, so called because there was a sacred tree inscribed with the cross of Christ there.[3] The tree was a testament to the way the Maya had integrated the Christian religion with their indigenous practices. Scholars might describe this integration as syncretism, but the Maya themselves saw it more like progressive revelation. Take for example, the prophecies of the Book of Chilam Balam which were written by a priest of the Maya religion in the late 1500s during the Spanish conquest of the Yucatan. Several texts included in the book assert that Christ is the highest god and that he would reign supreme over the Maya. At the same time, however, the Book takes pains to make clear that the old gods were real albeit “perishable” gods and that their worship had been proper.[4] Although the contents of their religious writings horrified the priests and bishops put over them, the Maya expressed quite clearly that they belonged to Christ and Christ belonged to them. Much of their prior practice, therefore, could be maintained with slight modification.[5] Their indigenous religious practices, for example, had a strong sense of the sanctity of nature and so the cross of Christ came to be associated with the ideas and practices of sacred trees.

This integrative and abrogative sense of prophecy forms the backdrop of a miraculous revelation to the gathered rebels. Defeated and fearful, the fighters were astonished when a cross appeared to them and began to proclaim aloud God’s love for them, the justice of their cause, and the need to continue the fight in the knowledge that God was with them. Some details of this first revelation are difficult to reconstruct, but a sort of priesthood and cult[6] of the Talking Cross seems to have sprung up immediately. It is evident, furthermore, that the religious experience revitalized the rebellion and became an essential part of the identity of the “Cruzob” or “cross people.”[7] The religious overtones of the conflict, clear from the outset, were heightened by the attempts of Spanish-descended clergyman to quell the rebellion. Long before the Cross spoke, priests appealed to the shared Christian identity of the Maya to encourage the rebels to lay down their arms. The Maya responded by asking them why they hadn’t considered God when they were murdering and abusing the Maya.[8] Later when the bishop complained that the rebellion was a symptom of growing secularism and lack of faith, the Maya pointed out that it was the “whites” who had burned and desecrated their churches.[9]

The Maya built a church at the cenote and placed within it three large crosses. The crosses continued to talk (through human actors), and the practices took on more distinctly Maya expression and belief.[10] The Maya dressed the crosses in traditional women’s clothing and a sort of hierarchy of crosses emerged with the adoption of local, familial, and personal crosses.[11] Crosses even came to replace the (typically white) images of saints, taking on the aspects of the saints they replaced.[12] The Talking Crosses, now physical and residing in a purpose-built church, soon began issuing proclamations and prophecies and even issuing letters to political and religious leaders signed “John of the Cross” or “John of the Cross Three Persons.” These are written in such a way as to make “John of the Cross” seem identical at points to the Cross itself, to Jesus, to God, and to the human caretaker of the Talking Crosses, leading to some uncertainty among scholars as to how to understand the exact identity of this “John of the Cross.”[13]

The text of several of these proclamations survive in multiple manuscripts in the Maya language.[14] They typically marry thunderous promises of Maya military success against the “Whites” with expressions of God’s concern for their suffering. The suffering of Jesus on the cross is frequently made parallel to the suffering of the Maya in their struggle for independence.

Because it has come,

The time

For the uprising of Yucatan

Over the Whites

For once and for all!

This is the reason

I am showing you

A sign

As a thing to be guarded in your hearts.

Because, as for me,

At all hours

I am falling;

I am being cut;

I am being nailed;

Thorns are piercing me;

Sticks are punching me

While I pass through

To visit in Yucatan;

While I am redeeming you,

My beloved (Proclamation of John of the Cross III,183-202)[15]

The Talking Crosses became the center of the rebellion and explicitly guided the warfare of the Maya through public declarations of the divine will about tactics and targets. Indeed, the cult was so central to the political success of the rebellion that factions among rebels even produced competing Talking Cross cultic centers.[16] Buoyed by the voice of the cross, the Maya rebellion succeeded in forming an independent state in the eastern Yucatan that would endure for 50 years. It was the most successful indigenous rebellion in the history of North America.[17]

A little more than a millennium earlier in the Kingdom of Northumbria, an area that straddles the border of present-day Scotland and England, a large stone cross around 18 feet high was raised in the village of Ruthwell.[18] This “Ruthwell Cross” bore intricate carvings of scenes from the life of Jesus and depictions of essential characters in his story. It also contained, etched in carefully placed runes, a poetic speech from the perspective of the cross, testifying to what it had witnessed. The same poem with slightly different wording is etched on a few other similar crosses erected elsewhere. It also survives as one of the rare longer Old English poetic works preserved in manuscript form.[19] The long version as recorded in the Vercelli Book has traditionally been called “The Dream of the Rood” and records a dream-vision in which the poet encounters a talking cross who reveals what it was like to witness and be forced to participate in the death of Jesus.[20]

The poem is full of pathos, expressing keenly the “tree’s” pain at being forced to stand still and upright as Christ’s blood is spilled upon it. The cross notes that were it granted leave by its master to do so, it could have killed all those who stood against him (36). Instead, the cross mirrors Christ’s obedience, enduring the misery of killing its lord and sharing in his wounding.

“I trembled as his arms went round me / And still I could not bend,

Crash to the earth, but had / to bear the body of God” (43-44)[21]

The cross is wounded by the same spikes which mount Jesus to the tree and shares in the shame and mockery heaped upon him (48). In a scene that marks a strange departure from the Gospels, it watches as a tomb is carved for Jesus (66) before it is ultimately itself buried in a pit. It then narrates its eventual discovery and adornment with gold and jewels (75-77).

This story of the discovery of the relic of the True Cross was popular in Old English sources and the Vercelli Book even contains a version where Constantine’s mother is supernaturally guided to it after Constantine defeats the Huns (!) with the sign of the cross.[22] The poem closes with a recounting of Christ’s victorious conquest over hell.[23] While the appeal to the cross’s direct testimony and the tendency to create “talking” stone crosses with parts of this poem are remarkable in themselves, even more so is the tendency to reframe Christ’s submissive death on the cross within the lens of the Germanic heroic tradition.

Scholars have long noted the way the poem presents Christ as a mighty warrior who chooses to suffer death in service to mankind. [24] Christ is explicitly called a “hero” twice in the poem and a “mighty prince” another time (39, 58, and 69). The warrior Christ “rushes forward” to the cross without fear and urgently completes his mission (34). The cross itself is portrayed as one of Christ’s thanes[25] which/who must suppress its own martial power in obedience to the will of its lord.[26] Christ, pierced as by arrows in battle, finds himself pinned to his thane which/who must patiently endure the sting of its master’s blood (34-49).

Other elements of pre-Christian Germanic religion assert themselves in the telling of this poem. The physical crosses contain carvings that echo imagery used in association with Yggdrasil the world tree of Norse legend.[27] These elements are also present in the longer manuscript form of the poem, most noticeably when the cross—which is described nearly exclusively with terms also used for trees—grows to a size where it overshadows the whole world (85).[28] This association was no doubt made easier by the fact that followers of Jesus had been referring to the cross as a tree from the earliest period of Christianity and longstanding tradition linked the cross with the great Tree of Life.[29] There are several surviving examples of living, botanical crosses in Anglo-Saxon art, showing that this association was fairly widespread. There is good evidence, moreover, that Christian missionaries to the Anglo-Saxons had to contend with a strong culture of sacred trees, and often responded by substituting crosses for sacred trees in an attempt to discourage traditional practices.[30]

If we bring these two talking crosses into dialog, it is interesting given their total independence from one another how parallel, in some respects at least, their interpretative retellings of the story of Jesus are. Most obviously and centrally, both employ the speech of the cross to allow the death of Jesus to speak directly to them. The cross thereby becomes a point of cultural negotiation, a conduit by which Christ can be made to feel what the community feels and to become in some sense part of the community. The cross, in other words, is a vehicle to make the death of Jesus for them. Why, though, a talking cross and not Christ speaking directly?

Perhaps the appeal lies in the curious blending of intimacy and separation. The cross is near enough to have felt what Christ felt but treated as a separate, personified entity it provides an unimpeachable direct witness without speaking for Christ. Perhaps it is simply the product of the emergence of the cross as a symbol. The cross as a symbol of the death of Jesus can accentuate the emotional resonance of self-sacrifice, becoming a place of pathos that can work cross-culturally by linking the common human experience of suffering to the suffering of Jesus.

The cross is also a symbol that inhabits multiple spaces. It exists conceptually in the ritual practice of imagining Jesus’s death and later physically in actual crosses or artistic depictions of the cross. Physical crosses when paired with ritual imagination, make the death of Jesus nearer, more tangible. The intimacy of the wood and the dying man become an intimacy shared with the audience which can see and touch that wood through representations of it.

The cross—whether physical or held in the mind—remains, furthermore, first and foremost an object and as such presents an opportunity for personification. The vacancy of sense and feeling in the thing personified allows it to effectively embody the thoughts and emotions of the personifier.[31] As an object, then, with both intimate “access” to Christ and an absence of any animating power, the cross becomes an opportunity for the expression of the community’s feelings and ideas. This potential is enhanced by the fact that the cross is also inherently imbued with polyvalent potential. It is at once a sign of Roman political power, of human mortality, of the interface between God and the created world, and so on. As a symbol, the cross weaves together multiple strands of meaning, threads which communities can pull upon to draw the story of Jesus into their story, to create a smaller second coming just for themselves.

These two talking crosses are in some respects the inheritors of a very ancient Christian practice of bringing the death of Jesus near. Paul preached in a manner designed to make the death of Jesus something that the community experienced such that he could describe his work as “placarding” Jesus Christ as crucified (Gal 3:1). A few decades later some Christians in Rome wrote a letter to some Christians in Corinth to intervene in a leadership struggle happening there. In seeking to persuade the Corinthians to end the conflict in their preferred manner, the Romans invited the Corinthians to join them in “staring intently at the blood of Jesus Christ” (1 Clem 7:4). The cross becomes very quickly, then, something to be experienced. This ritual imagination of the death of Jesus leads to the ritual experience of that death in baptism. Might we suppose, then, that the communal, ritual imagination of the death of Jesus was the precursor for the cross emerging as a symbol within the imagination (and slightly later still as a physically represented symbol)?

Perhaps our earliest talking cross offers us a clue. Written sometime in the second century, the Gospel of Peter famously portrays the moment of Jesus’s emergence from the tomb, narrating directly what earlier gospels omit.[32] Strikingly, the Gospel of Peter describes two angels entering the tomb and bearing out in some manner the resurrected Christ (9.34-10.39). Upon emerging from the tomb, the three swell in size until the heads of the angels touch the clouds and Jesus’s face is completely lost within them (10.40). Following along behind Jesus is the cross. When the voice of God asks, “Have you preached to those who are asleep?” it is the cross not Jesus which replies, “Yes” (10.41-42).[33]

While many of the distinctive elements here seem strange, Deane Galbraith has argued persuasively that they can be explained by a Christological yet overly literalized interpretation of the Septuagint (LXX) version of Psalm 18.[34] The enormous size of Jesus, for example, makes literal a metaphorical reference to the exultation of a running giant present in the LXX version of the psalm (LXX Ps 18:5).[35] The two speeches from heaven and the cross, likewise, are a double fulfillment of LXX Ps 18:1-2 akin to Matthew’s double fulfillment in Jesus’s ride into Jerusalem on both donkey and colt. The poetic parallelism of the heavens and the firmament declaring God’s glory become now a call and response in which God asks a question from heaven and receives an answer from the cross.[36]

In this schema, the cross stands in for the firmament. Galbraith shows that several texts from the second and third century associate Christ’s cross with the firmament by portraying it as the pillar or great tree that supports the sky.[37] The “cosmic cross” in these texts serves as a fundamental link between the earth and the heavens, drawing at points on the idea of Christ as a participant in the creation of the world and at points on the notion of the cross as a demarcation between heaven and earth. This latter notion is attested in both proto-orthodox and esoteric Christian sources, perhaps indicating that it is quite early.[38]

The Gospel of Peter’s interpretation of the cross as firmament is distinguished from these other examples of the “cosmic cross,” however, by the retention of the cross as a mundane object. The cross emerges from the tomb with Jesus, making clear that it is the very cross upon which he was crucified. Yet as the angels and Jesus become enormous, no such expansion is narrated for the cross. It retains its earthly characteristics even as it functions simultaneously as the “cosmic cross” of the (now Christologically interpreted) Psalm. The physicality of the cross, furthermore, offers a counterpoint to the display of divine power indicated by Jesus’s now gigantic proportions, allowing the earthly and glorified existences of Jesus to occupy the same frame.[39] By taking on this dual role, the cross as object—though one only held in the mind of the reader/hearer—now functions symbolically. It is both an actual cross and the cosmic cross which holds up the sky.

Context can illuminate the utility of juxtaposing earthly cross and glorified savior. The Gospel of Peter famously portrays Jesus as stoically and silently enduring his torments, a choice which has unfortunately led some to suppose that the work denies the reality of his physical existence.[40] One might conclude from this silent endurance that the pathos which so marked our other talking crosses is missing from this account, but it is simply more indirect. Rather than Jesus crying out, for example, the earth quakes in response to his injured body being laid upon it, suggesting creation protests his torturous treatment.[41] This is a sentiment that is presumably expected to be reflected by the audience. Jesus’s response to pain, rather, seems to be bound up in a narrative about Jesus’s power.

A key part of this power story in the Gospel of Peter is its unique form of Jesus’s “cry of dereliction” from the cross which replaces God with power. “Then the Lord cried out, ‘My power, O power, you have abandoned me’” (19). This apparent surrender follows and is presumably conceptually linked to Jesus’s incredible endurance of suffering. The declaration of powerlessness, however, is almost immediately undermined. Jesus is “taken up” right after his death, a fact that is even more remarkable given that when he emerges from the tomb he has just completed the harrowing of hell. It turns out, then, that the surrender of mortal power merely precipitates the expression of Jesus’s true power.

The Gospel of Peter pairs many elements in the crucifixion narrative with elements in the resurrection narrative—like, for example, the related verbs used to denote the lifting of the cross and the lifting of Jesus by the angels—which suggests that these scenes are mutually interpreting.[42] It is interesting then, that after the cry of surrender, the next statement from Jesus, albeit indirect, comes in the answer of the cross to God’s query. Discourses of power stand at both ends of a journey to heaven then hell and back again. The laying down of power inherent in accepting mortality, however, is not simply reversed. The Jesus which emerges from the tomb now shows in his glorified flesh the divine power which he possesses, made explicit by his gigantic size. To express it in traditional theological terms, the kenosis of the original incarnation is here partially eschewed by the glorified Jesus. This Jesus now manifests divine power on the earth, emerging from the tomb as an enormous, victorious conqueror. At the same time, the cross on which his unglorified body was crucified remains present as a crucial link to Jesus’s earthly life.[43]

It has been suggested that the alteration of Jesus’s cry of dereliction serves an apologetic aim, smoothing over an embarrassing part of the story. This may well be the case, but what if this discourse of power from a talking cross instead reflects the same sort of cultural negotiation we see in later talking crosses?[44] In other words, why might it be useful for a community to tell the story of Jesus in a way that particularly emphasizes Jesus’s victory over death and which takes pains to demonstrate Jesus’s enduring power over creation?

The earliest followers of Jesus lived in a world where people took the existence of spirits—both malevolent and beneficent—for granted. Places had spirits, homes had spirits, neighborhoods had spirits, rivers had spirits, and some spirits moved freely or with people. Early Christians integrated this spiritual reality with the teachings of Jesus in different ways, but many whether Jew or Gentile interpreted these beings as participants in the Jewish drama of angels and demons. Many early Christians thus show a particular anxiety about demons and demonic contamination, seeing themselves facing a dangerous tide of ever-present demonic beings.[45]

In this context, the ability of Jesus to exercise power over the earthly realm and its inhabitants is a grave matter of safety. The Gospel of Peter’s narration of the death of Jesus ironically emphasizes with his laying down of power the later reality of Jesus’s return as the divine warrior. In other words, the moment of his greatest weakness becomes, when viewed from the end, the beginning of his ascent to power. It is the cross as object, though, which testifies to his martial victory. Might we understand this cross, then, to now be functioning ironically as a symbol of Jesus’s power?

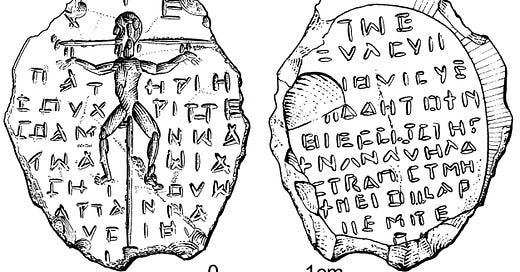

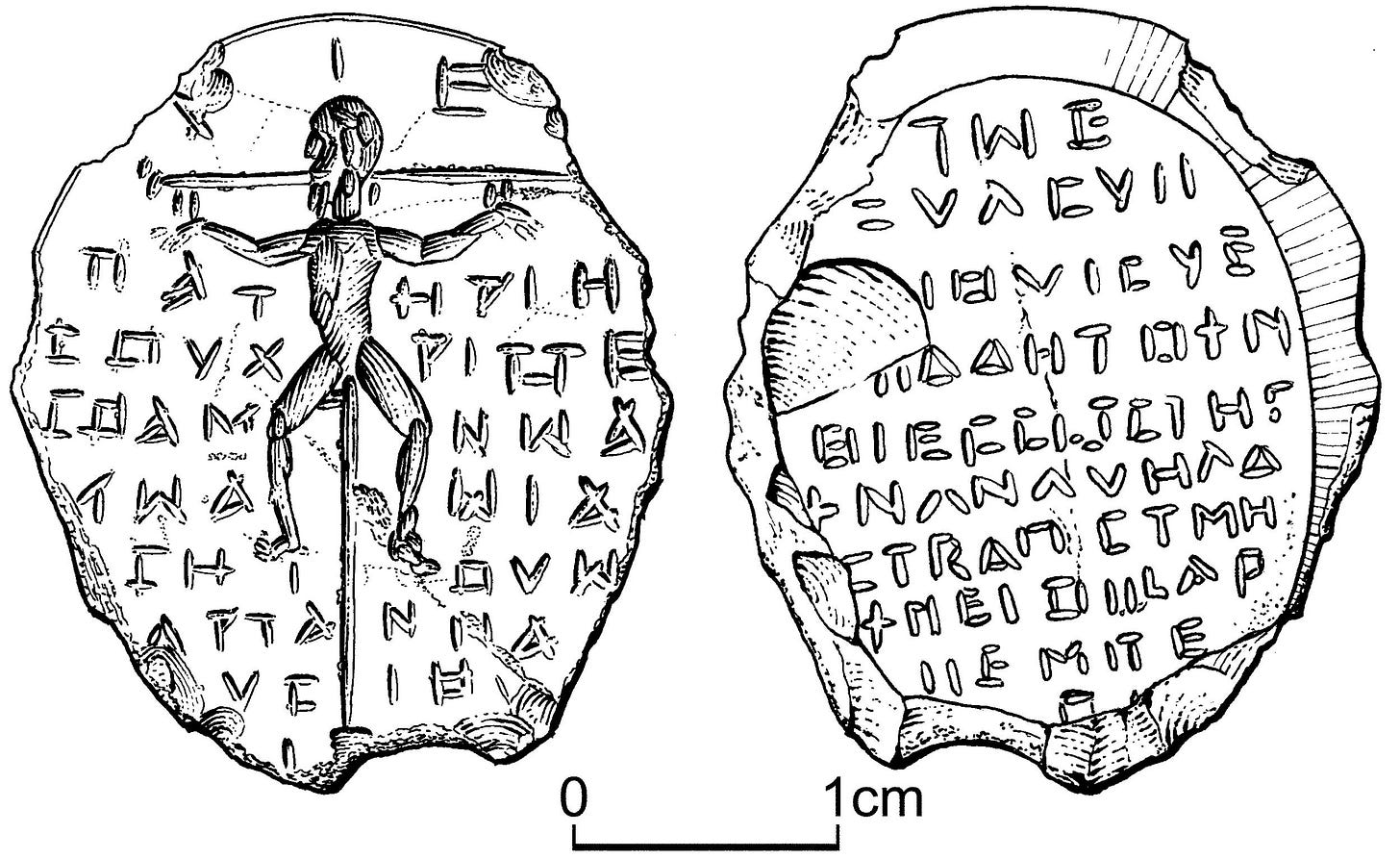

There is a parallel example of this inverted power dynamic in a symbolic and apotropaic context. Plausibly the earliest surviving depiction of the crucifixion is on a magical gemstone intended as a protective device.[46] The mottled red and black jasper gem (BM Inv. T 1986, 5-1,1)[47] depicts Jesus hanging on the cross surrounded by the words “O Son, O Father, O Jesus Christ,” then some magical words, then a reference to the cross, then perhaps the adjective for redeeming.[48] The back of the gem is inscribed with a series of names often invoked in exorcistic or magical contexts. Rather than simply using the word σταυρός, the gem employs a form of the poetic word ἀρτάνη which more generically denotes a thing by which something is hung up.[49] When considered alongside the visual exaggeration of the rope binding Jesus’s arm to the cross-beam, the wide splay of Jesus’s legs, and the apparent absence of any nails, the phrasing seems to emphasize strongly the sense of suspension or hanging.[50] As such, Roy Kotansky argues that the word in this case is best understood as a poetic term for the cross itself.

This is particularly of interest since Kotansky argues that it should be—following the pattern of names preceding—understood as a vocative. On this basis, Kotansky translates this and the following (partially reconstructed) words as an address to the cross, “O cross(-beam) of the Redeeming [S]o[n].”[51] While the use of the crucified Jesus as a defensive image is already notable, the direct invocation of the cross alongside Son, Father, Jesus Christ, and what appear to be magical names for god suggests that the cross itself was already understood to be a power capable of combatting evil. Given that Jewish and Christian elements are sometimes used in apparently pagan[52] magical objects (and vice versa), it is impossible to be certain if this gem was made for a Christian. Whomever it was made for, though, it is striking that the most powerful way to invoke Jesus for protection was to refer to the moment of his death. The moment of defeat here now is the symbol of Jesus’s ability to protect the bearer from harm.[53]

This association of the crucifixion with power over spirits or demons is also attested in second-century Christian written sources.[54] As part of a larger section explaining various titles and names ascribed to God by Christians, Justin Martyr makes the following remark about the name of Jesus:

For He also became man, as we stated, and was born in accordance with the will of God the Father for the benefit of believers, and for the defeat of the demons. [emphasis mine] Even now, your own eyes will teach you the truth of this last statement. For many demoniacs throughout the entire world, and even in your own city, were exorcised by many of our Christians in the name of Jesus Christ, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate[.] (2 Apol. 6.6)[55]

Jesus’s incarnation is partly for the purpose of defeating demons, a comment that only makes sense in light of Justin’s allusion to what seems to be an exorcistic formula, “In the name of Jesus Christ, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate.” Already, then, the crucifixion is seen as having particular import for Christ’s conquest of the demonic powers such that it is evoked directly in confrontations with demons. This might seem like an obvious thing to do, but given the tendency in exorcistic formulas to evoke beings in a state of power or glory like angels and other divinities it is notable that it is Christ’s past dying that is called upon and not the ascended, glorified present reality.

That this is a fixed formula is made clear by the numerous repetitions of the phrase in Justin’s writings in exorcistic contexts (Dial. 30, 76, 85; 1 Apol. 61 in a baptismal but probably still exorcistic context) as well as the appearance of the phrase in Irenaeus in the context of wonder working and healing (Haer. 2.32.4).[56] In one of these passages from the Dialogue with Trypho, we find a comment reflecting the anxiety of demonic assault mentioned above followed by explicit reference to the use of this phrase as an exorcistic formula.

Furthermore, it is equally clear…that we believers beseech Him to safeguard us from strange, that is, evil and deceitful spirits. We constantly ask God through Jesus Christ to keep us safe from those demons who…were once adored by us…We call Him our Helper and Redeemer, by the power of whose name even the demons shudder; even to this day they are overcome by us when we exorcise them in the name of Jesus Christ, who was crucified under Pontius Pilate, the Governor of Judea. Thus, it is clear to all that His Father bestowed upon Him such a great power that even the demons are subject both to His name and to His pre-ordained manner of suffering. [emphasis mine] (Dial. 30)

In this passage, Justin not only employs the exorcistic formula, but he makes explicit that the demons are subject to the cross itself which shares in Jesus’s martial power over evil spirits. The mere calling to mind of the image of the cross with Jesus upon it is enough to drive demons from people. This ekphrastic power over demons seems to extend also to broader visual realms. Tertullian remarks in De Corona, for example, that the Christians in Carthage continually trace the sign of the cross upon their foreheads to protect themselves from demons (Cor. 3). This ritual of protection brings the cross into the present and draws it near by making the body its canvas.

If we consider the Gospel of Peter’s resurrection scene in light of the reality that the cross and crucifixion were seen both defensively and offensively as particularly potent against demons, then the walking, talking cross takes on additional significance. The earthly cross of Jesus stands stark, emerging from the tomb in victory, and declares the dominance of the now magnified Christ. This cross—the same earthly cross viewed in the ritual imagination of Jesus’s death and maybe already present physically on apotropaic devices—is situated alongside the glorified Christ and declares in fulfillment of prophecy that the one who had said “O My Power” now returns in power. By having the answer to God’s question come from the cross rather than, as expected, directly from the risen Lord, the author emphasizes the enduring impact of the victory just achieved.

The presentation, then, preserves and unites both the symbolic role of the “cosmic cross” and the visual-apotropaic role of the earthly cross. In doing so, the author ensures that the last image of Jesus in the Gospel of Peter communicates the enduring power of Christ, using an absence in the Gospels to make present the death of Jesus. The reversal offered by the walking, talking cross not only transforms it into the cross of victory but also draws that power near so that the community can take hold of it for themselves. The story of Jesus’s death and resurrection becomes, thereby, a story about both his power and theirs. In the inescapable sea of demons they perceived around them, they need not fear for they already possessed victory.

Whether in the Yucatan in the 1800s or England in the 700s or Syria (?) in the 100s CE, then, it seems the story of the talking cross is a story about apprehending, a story of making meaning with the death of Jesus and a story of making use of the death of Jesus. The abject Christ and the glorified conqueror, existing together in the same space, are drawn near to the community. Power and suffering mingle together like wine and gall to numb pain with understanding and terror with hope. The symbol of death now animated brings life. What is mute is made to speak for the divine and in so doing speaks of what is human.

[1] The most accessible overview can be found in Victoria Reifler Bricker, The Indian Christ, the Indian King: the Historical Substrate of Maya Myth (Austin: UT Press, 1981), 87-118 but note the additional nuance offered in Don E. Dumond, “The Talking Crosses of Yucatan: A New Look at Their History,” Ethnohistory 32 (1985): 291-308.

[2] Bricker, Indian Christ, 89-94.

[3] Bricker, Indian Christ, 103 provides an image of the tree though the inscribed cross is not visible in it.

[4] A good example of this is the creation narrative which fully integrates the Maya creation myth with the biblical creation myth by suggesting that God the Father had created the other gods who were nevertheless to pass away later when Christ comes. See Ralph L. Roys and Juan José Hoil, The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. (Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1933), 98f. Accessible here.

[5] There is evidence that this flexibility was a long-standing trait of Maya religion as Nahua gods were integrated into Maya belief after Nahua conquests. Roys and Hoil, Book, 201.

[6] The word “cult” is used here in its academic sense and not in a pejorative manner.

[7] Bricker, Indian Christ, 104f.

[8] Bricker, Indian Christ, 94.

[9] Bricker, Indian Christ, 100.

[10] When the church was later sacked by the Yucatan government, they found a large barrel had been sunk into the floor allowing a human to speak for the crosses in a booming, resonant voice. There is some evidence that rather than a deception, this fact was widely known to the worshippers as the identities of those who spoke for the crosses seems to have been general knowledge or at least wider than one might expect. See discussion in Dumond, “Talking Crosses,” 295-298.

[11] Bricker, Indian Christ, 108; Dumond, “Talking Crosses,” 295.

[12] Bricker, Indian Christ, 113.

[13] Dumond, “Talking Crosses,” 294; 304n12.

[14] The strong literary culture of the Maya has allowed scholars unparalleled access to their evolving beliefs.

[15] Bricker, Indian Christ, 192-3.

[16] Dumond, “Talking Crosses.”

[17] Bricker, Indian Christ, 87.

[18] For a helpful overview of the contents and core questions around the Ruthwell Cross, see Clare Stancliffe, “The Riddle of the Ruthwell Cross: Audience, Intention, and Originator Reconsidered” in Crossing Boundaries: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Art, Material Culture, Language and Literature of the Early Medieval World (eds. Eric Cambridge and Jane Hawkes; Philadephia: Oxbow Books, 2017).

[19] For a discussion of the relationship and shared religious context of these related texts, see Éamonn Ó Carragáin, Ritual and the Rood: Liturgical Images and the Old English Poems of the Dream of the Rood Tradition (London: The British Library/University of Toronto Press, 2005).

[20] The contents of the Codex were chosen based on the theme of the cross and carefully organized. For an overview and helpful discussion of interrelationships between texts in the codex, see Éamonn Ó Carragáin, “The Vercelli Book as a Context for the Dream of the Rood” in Transformation in Anglo-Saxon Culture: Toller Lectures on Art, Archaeology and Text (eds. Charles Insley and Gale R. Owen-Crocker; Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2017), 108-126.

[21] Translation from Burton Raffel, Poems and Prose from the Old English (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998).

[22] The poem, called Elene, confuses Constantine’s battle against Maxentius at the Milvian Bride in 312 CE with the Battle of Châlons in 451 CE. The latter battle featured an alliance of Western Romans with Visigoths and an assortment of Germanic “barbarian” tribes who gathered together to stop Attila the Hun. The battle with Attila was remembered in Germanic legendary material about the mighty Atli who became a principal antagonist of the hero Sigurd in the Volsung saga. See Appendix A (pgs. 337-348) by Christopher Tolkien in J. R. R. Tolkien, The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009).

[23] Though some scholars argue whether the harrowing of hell or the second coming are in view. See the argument that the poem refers here to the Last Judgment in Monica Brzezinski, “The Harrowing of Hell, the Last Judgment, and ‘The Dream of the Rood’,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 89 (1988): 252-265.

[24] The literature is extensive. A concise and frequently cited example is Carol Jean Wolf, “Christ as Hero in ‘The Dream of the Rood’,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 71 (1970): 202-210.

[25] A thane or thegn is an upper class or noble landholder who is pledged to a ruler. They are roughly equivalent to what we might call a knight or retainer. In northern Germanic and Anglo-Saxon literature, thanes often serve as trusted warriors who battle alongside their lord.

[26] Wolf, “Christ as Hero,” 203.

[27] G. Ronald Murphy, Tree of Salvation: Yggdrasil and the Cross in the North (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 125-153.

[28] Murphy, Tree.

[29] Already in the New Testament: Gal 3:13; Acts 5:30, 10:39, 13:29; 1 Pet 2:24. On the “verdant cross,” the Tree of Life, and the connection of this tradition to Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian art, see Della Hooke, “Christianity and the ‘Sacred Tree’,” in Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World (eds. Michael D. J. Bintley and Michael G. Shapland; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 228-247.

[30] Clive Tolley, “What is a ‘World Tree’, and Should We Expect to Find One Growing in Anglo-Saxon England?” in Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World (eds. Michael D. J. Bintley and Michael G. Shapland; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 177-185.

[31] The link between emotion and personification was already recognized by the writers of the ancient treatises on rhetoric who note the utility of prosopopoeia for generating pathos.

[32] I presume the familiarity of the Gospel of Peter with at least the Synoptic Gospels.

[33] All quotations from the translation of Simon Gathercole in The Apocryphal Gospels (Penguin Classics; Penguin Random House, 2021).

[34] Deane Galbraith, “Whence the Giant Jesus and his Talking Cross? The Resurrection in Gospel of Peter 10.39-42 as Prophetic Fulfillment of LXX Psalm 18,” New Testament Studies 63 (2017): 473-491.

[35] Galbraith, “Giant Jesus,” 483-486.

[36] Galbraith, “Giant Jesus,” 480-483.

[37] Galbraith, “Giant Jesus,” 487-490.

[38] Galbraith, “Giant Jesus,” 489-490.

[39] If one accepts that the cross literally is Jesus and that this is a polymorphic presentation of Christ, then the sense is heightened though this is not necessary. See note 42 below.

[40] Peter Head has noted that this sort of incredible endurance of pain is a common feature of martyrdom accounts from the second and third century and is clearly not meant to communicate only the appearance of suffering. Peter M. Head, “On the Christology of the Gospel of Peter,” Vigiliae Christianae 46 (1992): 211-213.

[41] Paul Foster, “The Gospel of Peter,” Expository Times 118 (2007): 321. Unfortunately, I do not presently have access to Foster’s commentary.

[42] Noted briefly in Jason R. Combs, “A Walking Talking Cross: The Polymorphic Christology of the Gospel of Peter,” Early Christianity 5 (2014): 205-206. The connections between the two scenes are discussed in detail in Robert G.T. Edwards, “The Theological Gospel of Peter?” New Testament Studies 65 (2019): 496-510.

[43] Alternatively, if one accepts a polymorphic view, the glorified and the earthly stand together. For the full argument see Combs, “Polymorphic Christology.”

[44] While the religious experience in the Yucatan is clearly independent, the Dream of the Rood might be dependent directly on the Gospel of Peter or be familiar with some of its traditions. The case has been made in A. D. Horgan, “‘The Dream of the Rood’ and Christian Tradition,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 79 (1978): 11-20. While there are some clear divergences between the documents, particularly as to the fate of the cross, the dependence is plausible given the frequency with which Old English sources show familiarity with Apocryphal traditions. Scholars have argued that the Dream of the Rood in particular shows familiarity with numerous apocryphal texts including the Gospel of Nicodemus and the Passio Andreae. Robert E. Finnegan, “The Gospel of Nicodemus and ‘The Dream of the Rood’,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 84 (1983): 338-343; Thomas D. Hill, “The Passio Andreae and The Dream of the Rood,” Anglo-Saxon England 38 (2009): 1-10.

[45] Consider, for example, Tertullian’s concerns for the ever-present threat of demons. Travis W. Proctor, Demonic Bodies and the Dark Ecologies of Early Christian Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 144-170.

[46] Possibly dating as early as the late second century. See Felicity Harley and Jeffrey Spier, “Magical Amulet with the crucifixion,” in Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art (eds. Jeffery Spier and Kimbell Art Museum; Yale UP, 2007), 228 cf. Jeffery Spier, Late Antique and Early Christian Gems (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2007), 72-75. Depending on how one dates things, the Alexamenos Graffito may well be the earliest or at least roughly contemporary. For an overview of research on the graffito as well as the notable parallels in iconography to this gem, see Felicity Harley-McGowan, "The Alexamenos Graffito," in The Reception of Jesus in The First Three Centuries (ed. Chris Keith; T&T Clark, 2019), 105-140.

[47] =Spier, no. 443| BMC Magical Gems, no. 457

[48] See the detailed analysis in Roy D. Kotansky, “The Magic ‘Crucifixion Gem’ in the British Museum,” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 57 (2017): 631-659. Kontansky argues (648-649) that the magical names on the back of the gem are by a different engraver and so were presumably added later, though others see them as original. Kotansky argues on this basis that the producers were Christians and the usage of “mystical” or “magical” elements is more “hymnic and invocational than magical.” This conclusion is strange since Kotansky earlier relies upon Christian magical texts to establish his interpretations of the inscription. Moreover, the usage of this gem within a ritual like baptism (one of the possibilities mentioned by Kotansky) does not by any means preclude an apotropaic or otherwise magical purpose.

[49] Kotansky, “Gem,” 644f.

[50] Kotansky, “Gem,” 646. Bruce Longenecker has argued that the depiction suggests a manner of crucifixion similar to that which was suffered by the famous Yehohanan whose ossuary contained his ankle bone with the crucifixion nail still in it. Jesus’ legs, however, are presented as quite distant from the cross. Bruce Longenecker, The Cross Before Constantine (Fortress Press, 2015), 101-104.

[51] Kotansky, “Gem,” 635, 647-648.

[52] Since the word pagan originates as a pejorative term for traditional polytheistic religion during the Christianization of Rome, I want to note that no pejorative meaning is intended here. The term pagan is employed merely for convenient brevity.

[53] I am not suggesting that the author necessarily knows this or a similar amulet. It is interesting, nonetheless, that both this object and the Gospel of Peter have been hypothesized to have originated in Syria.

[54] For a general overview, see David Aune, “Magic in Early Christianity,” ANRW 23.2: 1507-1557 and 1547-49 for a discussion of these examples.

[55] All translations of Justin Martyr from Thomas B. Falls, Justin Martyr (Fathers of the Church 6; Washington, D.C.: CUA Press, 1965).

[56] This is cited as 2.49.3 in Aune and in sources apparently dependent on him. I am not sure if this is an error or if it refers to a numbering system with which I am unfamiliar.

This was great, Jeremiah! Really enjoyed the deep dive into other talking cross traditions as a way to think about GP. Had heard about these other traditions, but hadn't seen them put in such rich conversation with the earlier material, as you do.